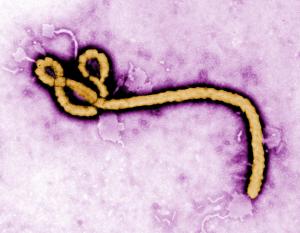

I am currently listening to an audiobook entitled Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel which features a super-virus with the sweet sounding name of the Georgia Flu (since patient zero is from Russia). This flu is apparently much worse than the Ebola virus rampaging through West Africa since it is airborne and has a gestation period of only a few hours. In Mandel’s apocalypse, the hospitals fill up exponentially throughout perhaps a few days until things break down completely and it’s all over for everyone but a small percentage of humanity; poor bastards who happen to be immune. Sound familiar? Stephen King’s The Stand begins similarly. But in King’s epic there is a strange force drawing the survivors to a central location somewhere in the US.

I am currently listening to an audiobook entitled Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel which features a super-virus with the sweet sounding name of the Georgia Flu (since patient zero is from Russia). This flu is apparently much worse than the Ebola virus rampaging through West Africa since it is airborne and has a gestation period of only a few hours. In Mandel’s apocalypse, the hospitals fill up exponentially throughout perhaps a few days until things break down completely and it’s all over for everyone but a small percentage of humanity; poor bastards who happen to be immune. Sound familiar? Stephen King’s The Stand begins similarly. But in King’s epic there is a strange force drawing the survivors to a central location somewhere in the US.

Reading

concerning the process of reading.

On Gothic Horror

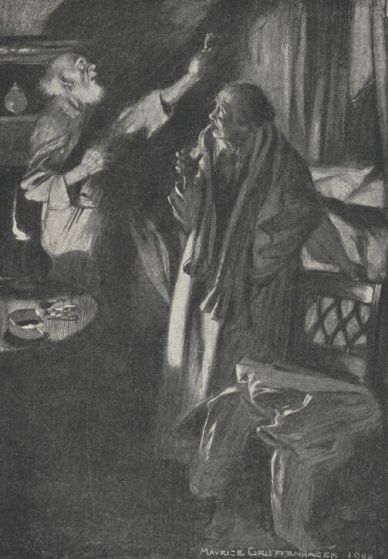

Melmoth the Wanderer

I recently read Irish clergyman C.R. Maturin’s send-up of the Gothic Horror genre, Melmoth the Wanderer, which was originally published in 1820, twenty five years after Ann Radcliffe’s seminal novel of Gothic Romance, The Mysteries of Udolpho, and only two years after Mary Shelley’s uber-classic Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus. I am more piqued than ever by literature of this ilk and its influence through to the present day; not that I haven’t always been interested in the dark and more seamy hues of story-telling, but Melmoth has refocused me. The Faustian tale is truly a parody like much of the hyperbolic genre; what’s not to like about a school of writing that refuses to take itself too seriously.

125 Essential Literary Works (that I’ve read so far)

This list was published in its original form as the 100 Most Personally Influential Books on my Book Jones Review blog back in 2009. It is, as a matter of course, limited to books I have read. I have updated it here as 125 Essential Literary Works (that I’ve read so far) for 2014. Below is the complete list. I will subsequently post partial lists to include my thoughts, comments, links, etc… on each book. Do you agree, disagree? What would you add or delete from the list. Feel free to comment. Enjoy.

Continue reading “125 Essential Literary Works (that I’ve read so far)”

Nachman, Is That You?

There has been a slight resurgence of the short stories of Leonard Michaels who passed away in 2003. What do I consider a slight resurgence? Well, it is quite a subjective statement, based solely on the podcasts I consume. The New Yorker Fiction July 2014 podcast features Rebecca Curtis reading The Penultimate Conjecture, one of a septet of stories dubbed the Nachman Stories written by Leonard Michaels near the end of his life. Another podcast, Selected Shorts from PRI recently presented a program in honor of the late David Rakoff where Mr. Rakoff performs Cryptology, the last story in the Nachman septet, at Symphony Space in New York City.

Leonard Michaels’ writing has been compared to Isaac Babel, Bernard Malamud, and Philip Roth. His protagonist, Nachman, is a world-class mathematician originally from Cracow, living in Los Angeles. He hates to travel, doesn’t particularly get along with too many people, he ironically seems more suited to New York than to L.A. The Penultimate Conjecture follows Nachman to San Francisco where he is attending the annual meeting of the Pythagoras Society. There, a young Scandinavian Mathematics colleague, Bjorn Lindquist, is expected to layout his solution for the infamously difficult math proof, the Penultimate Conjecture, which British cryptographers formulated during the second world war. At the upstart’s presentation, Nachman meet’s another math wizard, a Russian by the name of Chertoff (which means something diabolical in the Slavic language) , who urges Nachman to reveal what he knows is true in his heart: that Lindquist’s solution is flawed.

In Cryptology, we find Nachman out of his comfort zone again, this time in NYC to attend the annual cryptology conference. He meets an old friend (“I’m Helen Ferris now”) on Fifth Avenue, a woman whom he simply cannot place. After handing over her address and apartment keys to Nachman, she invites him to dinner with her and her husband: “If you arrive before us, just wait in the apartment,” she tells him. But when Nachman arrives at the posh Chelsea flat he finds it deserted; until he perceives the faint hiss of a shower and voices carrying from the next room. Cryptology is a story infused with mystery, both outward and inward. By the end Nachman is musing on not just who Helen Ferris could be, but who he, the enigmatic Nachman, really is.

All of the Nachman stories can be found in: The Collected Stories by Leonard Michaels

Shorties

The short story, at least in America, has vacillated in popularity since its virtual birth as a literary art form (storytelling, long or short, has existed ever since primordial humans gathered in caves around the fire) in the early19th century. Writers like Charles Dickens, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Washington Irving were among the progenitors of the form. Edgar Allan Poe wrote many popular stories between 1832 and 1849 including what is widely recognized as the first ever mystery story, The Murders in the Rue Morgue, which features detective Auguste Dupin and an ape. Poe, in his 1846 essay The Philosophy of Composition, argues for the brevity of all literature, novels and poetry included: “It appears evident, then, that there is a distinct limit, as regards length, to all works of literary art – the limit of a single sitting” he writes, and by so doing, presumes the short story to be not merely the highest form of literary art; but perhaps, with a few exceptions, the only literary form with any artistic effectiveness in his view.

I’ve always been interested in short stories, even as many like-minded readers cast off their tolerance for the form citing insufficient plot immersion or unmemorable characters. There is something about a well written short story that can move the reader more intensely than, say, a 350 page novel. A short story will demand more of a reader, just as a masterfully directed film will of its viewers: by way of omission. The short fiction reader is required to fill in the blank spaces, enhancing the reading experience. In many classic tales it is indeed what is not said that affects one the most. I’m thinking of the classic spinetingler The Monkey’s Paw by W.W. Jacobs which I remember reading back in high school and recently heard performed by John Lithgow. In this perennial classic, after returning from the exotic far east, a family friend reluctantly reveals a mysterious artifact: an all too real and distinctly creepy monkey’s paw. Soon he divulges its powers to the family (a married couple and their adult son): Three wishes will it grant – which reminds the mother of the Tales of the Arabian Nights. Destroy it, cast the paw in the fire, warns the friend, for it will only bring you grief. But of course, before long the family is wishing away. After the first wish, their son meets with a grisly end. Jacobs does not go into any gory detail, though enough gore is hinted at. After the second wish, we only hear the terrible rapping, like Poe’s Raven, on their chamber door, and by the third wish, we are so terrified, Jacobs need not even verbalize it. It is superfluous to the effect.

Other memorable stories from my early reading include Shirley Jackson’s The Lottery, O’Henry’s The Cop and the Anthem and William Faulkner’s A Rose for Emily. I like to believe my tastes matured a bit through my teens and twenties with the appreciation of the complex grotesques of Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio and the wonderfully uneven Nine Stories of J.D. Salinger. One of my all time favorite short fiction writers to date is T. Coraghessan Boyle. who happens to be a wizard of black humor, irony, and the brutal ending. Boyle can be read regularly in the New Yorker magazine along with other of the best in the genre today: Alice Munro, William Trevor, George Saunders, Laurie Moore and Tobias Wolff to name just a few. His latest concise tale published in that storied (forgive the pun) journal, is a gem titled The Relive Box, which takes place in an alternate present-day reality and features an immersive device which allows one to relive, as a spectator, any slice of one’s past life one may specify. So you can imagine just how obsessed Boyle’s protagonist may become. With a mere five to six thousand words, Boyle is able to move me (and I’m sure countless others), to tears. Why? He evokes memory; and human memory in its basest form is where all pain and joy lurk like forgotten athletes just waiting to be called off the bench to re-enter the game. It shouldn’t take an entire novel to release those devastating bench warmers, just a few carefully crafted sentences.